The Story of Contemporary First Nations' Art: Part 3

WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers are warned that the following article may contain images of deceased persons.

In the 1980s and 1990s, First Nations’ art took the western art world by storm. Major Australian exhibitions increasingly included their art, national institutions acquired artworks for their collections, and exhibitions at major international galleries drew critical acclaim. A turning point occurred here where Aboriginal art started to be seen as contemporary art, rather than tribal, native, ethnographic or traditional art. During this period, many Indigenous-run art centres were established in remote communities, and were driven by artists and elders, and supported by non-Indigenous experts.

The Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery, in Fitzrovia, central London, was the first art gallery in Europe to exhibit Australian Aboriginal art. Hossack’s gallery was also the first in London to exhibit the myth of the Wandjina, which are sky spirits associated with weather for First Nations’ people in the Kimberley region of Western Australia. The gallery has worked with celebrated artists from this region such as Lily Karedada, Queenie McKenzie and Rover Thomas. An extensive variety of beautiful, intricate pieces - from paintings on bark and canvas to lino prints, basket-works, sculptures and carvings - would have never been seen in the UK if not for Hossack’s initiative (Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery, 2020).‘The Independent’ (2004) British online newspaper established in 1986, stated that Hossack was one of the significant figures responsible for:

“...bringing an awareness of Aboriginal culture to this country...the Australian art dealer Rebecca Hossack, who, for many years, has brought images created by the Indigenous peoples of her homeland to a wider audience, educating us in the “Dreamings” and myths that form the essence of their being.”

Lily Karedada’s ‘Ponnai Wandjina,’ 1996, screenprint. Image courtesy of Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery, 2020.

Hossack (2020) recalled her decision to open her gallery in 1987:

“The inspiration and impetus behind this venture was my desire to show Aboriginal art in London, as it was at the time relatively unknown.”

The Melbourne-born art dealer is an acknowledged expert in the field. Hossack writes regularly in the press (The Independent) about Aboriginal art, and between 1994 and 1998 she served as Cultural Attaché at the Australian High Commission in London to promote Aboriginal art even more broadly across the UK. Hossack has been in awe of Aboriginal art ever since the emergence of the Papunya Tula Desert Painting movement during the 1970s-80s. Her gallery promotes Aboriginal art through its annual ‘Songlines’ exhibitions in London and the US. In these exhibitions, she shows artworks by leading artists from communities she has worked with over the years, such as: Yuendumu, Lajamanu, Balgo Hills, Papunya, Spinifex, Ngukurr, Yirrkala, Warmun, Ampilatwatjari, Maningrida, Fitzroy Crossing, Elcho Island, Tiwi and Borroloola. Further, she exhibits ground-breaking solo shows of leading First Nations artists including Clifford Possum, Emily Kame Kngwarrey, Jimmy Pike, and more recently, Ningura Napurrula, Anatjari Tjakamarra and Nyurapayia Nampitjinpa.

Clifford Possum’s ‘Warlugulong,’1977,synthetic polymer paint, oil and natural earth pigments on canvas. Bought by the National Gallery of Australia for a record-breaking $2.4million. Courtesy of NGA, 2020.

Hossack has been instrumental in providing many First Nations artists with once-in-a-lifetime opportunities to build their profiles and reach an international audience. For example, the art dealer works closely with public institutions and galleries to further promote Aboriginal art, arranging exhibitions in public spaces, and making sales to world-renowned museums, such as the Victoria and Albert Museum, the British Museum, the Gallery of Modern Art, and the De Young Museum in San Francisco.

The majority of the artists Hossack has worked with have been invited to London for their exhibitions, and in 1990, she memorably brought Clifford Possum to Buckingham Palace to meet the Queen where he presented Her Majesty with one of his paintings. In 1988 and 1990, Clifford came to London for his solo exhibitions, and in 1997 he provided a design for the tail-fins of the re-branded British Airways fleet. Eight years later, when Hossack arranged for Spinifex artists Jimmy Pike and his wife Pat Lowe to visit London, Jimmy insisted on visiting Captain Cook's simple little house in Whitby to "go and see where the trouble started" (Rebecca Hossack, 2020).

Clifford Possum with his design for the British Airways fleet tail-fin design in 1997. Image courtesy of Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery, 2020.

Emily Kame Kngwarreye

Emily Kame Kngwarreye’s (born 1910) artwork is an example of the incredible level of international respect that was achieved by the contemporary Aboriginal art movement. This tiny Utopian woman in her eighties was from the desert area of Alhalkere (Soakage Bore), north-east of Alice Springs. Emily held the significant title of tribal elder for her Utopian community, and thus was the keeper of several sacred song-cycles, such as the Yam and Emu Dreaming. She was well-educated in the tribal wisdom of her people, and learnt stories and ceremonies that combined topographical information, gastronomic hints and creation myths. This incredibly talented elder became world-renowned for being the greatest First Nations contemporary artist (Rebecca Hossack, 2010).

“She carried Aboriginal art beyond the limited sphere of ethnographic curiosity into the broad stream of contemporary culture," Hossack (2020) described to The Independent.

Emily Kame Kngwarreye. Image courtesy of NGA, 2020.

In 1977, Emily's local women's group was encouraged, by linguist Jenny Green, to transfer her tribe's traditional body decoration and ceremonial motifs onto silk. Despite Emily being in her late sixties by this stage, she approached this new activity with such dedication and passion. Under the authority of a new art-adviser, Rodney Gooch, in the summer of 1988-89, the women’s group began experimenting with acrylic paints on canvas. Since Emily claimed to have always disliked the fumes of the batik-wax, she responded enthusiastically to the greater freedom this medium provided. From here, she painted the flora and fauna of her country, their life-cycles and mythical meanings, right up to the week of her passing at Soakage Bore. What made Emily’s paintings distinctive was her bold sense of composition and feel for colour (Rebecca Hossack, 2010).

In Emily’s earlier works she employed the use of linear patterns, overlaid by careful dotting. Her technique of cutting the bristles of her paintbrushes short to create wider, hollowed dots was followed by, in 1992, the use of freer, bold circular dabs of paint, often double-dipped into different colours before applying to the canvas. These creative techniques allowed her to create an intense sense of the desert’s reverberating light and colour (Rebecca Hossack, 2010). In 1994-5, Emily rapidly shifted her style to simple strokes of black and white stripes and organic traceries on dark backgrounds. Hossack (2010) verbally illustrated Emily’s painting technique to The Independent:

“She worked sitting on the ground with her canvas held close to her body, while she dabbed on the paint with an economic intensity. She worked from the outside inward, turning the canvas gradually, and changing her brush hand to facilitate the task.”

Emily Kame Kngwarreye’s ‘Untitled: Alalgura Landscape/Yam Flowers,’ 1993, Utopia Community. Image courtesy of the Rebecca Hossack Art Gallery, 2010.

As soon as Emily’s artworks were discovered, public galleries and private collectors from Australia and from around the world were quick to acquire her works. She exhibited tremendously successful solo shows across Australia and London. In 1992, Emily received the Australian Artist’s Creative Fellowship, worth $110,000, and in 1995, she was granted the rare accolade of a solo show at Parliament House, Canberra. Further, she was chosen as one of the three First Nations female artists to represent Australia at the 1997 Venice Biennale.

As the millennium came about, both prices and sales for First Nations’ art boomed, and Emily’s ‘Earth Creation’ (1994) sold for over $1million. The constant demand for her works from art-dealers world-wide and from her own extended family resulted in her earnings of as much as $500,000 a year. As clan elder, Emily was responsible for as many as 80 kins-people, whom she happily divided her money amongst, according to her traditional practice (Rebecca Hossack, 2010).

“Despite her wealth, she continued to live the traditional Aboriginal life, gathering bushtucker, and sleeping under the stars in her bough-shelter at Soakage Bore. She was part of the country she painted," said Hossack (2010).

Emily Kame Kngwarreye’s ‘Earth’s Creation,’ 1994, synthetic polymer paint on linen mounted on canvas. Image courtesy of Khan Academy, 2020.

Rover Thomas

Another instrumental First Nations’ contemporary artist is Rover Thomas, a Wangkajunga man from Gunawaggi, Western Australia. Similarly to many Indigenous people at this time, he worked as a stockman at Billiluna Station in the Kimberley region without pay for many decades. This was until the mid-1970s when the Australian government made the ruling that all Aboriginal pastoral workers must receive the same wages as their white co-workers. Many Indigenous people lost their jobs here as station owners claimed they couldn’t support this measure, and so Rover and many others moved to Warmun, an Aboriginal community at Turkey Creek (Rebecca Hossack, 1998). Hossack (1998) recalled a story Rover informed her of, which was a turning point in his life:

“...he received several visitations from the spirit of a relative who had recently died following a truck accident. She recounted the story of her death in terms of the mythological landscape of the area and revealed to Thomas a new ceremony cycle - the Krill Krill.”

From here, Rover began to paint, and it was on boards for the Warmun community’s Krill Krill ceremonial dance rituals. Rover’s drawing on the traditions of East Kimberley ceremonial body-painting and rock art produced extraordinary, original artworks. He worked with natural ochres from the Kimberley region, mixing and grinding them himself, and painted aerial perspectives. Aerial perspectives are common to many Aboriginal desert art paintings. When you see U-shapes in a circle, it represents human presence, which usually depicts the imprint of buttocks when clanspeople are sitting cross-legged in the sand in the desert. Rover’s painting extended beyond ceremonial boundaries where he recorded his residing landscape, its Dreamtime significance and its racially troubled history (Rebecca Hossack, 1998).

Rover Thomas’ ‘Ruby Plains Killing 2’ (1990), from ‘The Massacre,’ natural pigments on canvas. Image courtesy of NGA, 2020.

With the success of the Western Desert Art movement, Rover’s paintings were soon acclaimed by critics and collectors. The East Kimberley artist exhibited throughout Australia and in the United States, Canada, France, Italy, Germany, Britain and Japan. In 1994, Rover became one of the first Aboriginal artists to have a solo exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia (Rebecca Hossack, 1998).

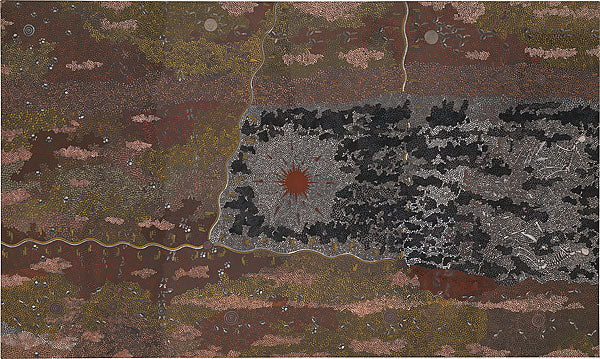

Rover Thomas’ ‘Julama -All That Big Rain Coming From the Top Side, ’ 1991, natural earth pigments and synthetic binder on canvas. Image courtesy of Cooee Art, 2001.

Ginger Riley Munduwalawala

Ginger Riley Munduwalawala’s ‘Limmen Bight River Country,’ 1992, synthetic polymer paint on canvas. Courtesy of the Art Gallery of NSW, 1992.

As a young man in the 1950s, Riley met the celebrated watercolourist Albert Namatjira when he was driving cattle in Alice Springs. Albert’s colourful depictions of the desert landscape made a great impression on Riley, and he hoped to one day depict his own country in such a way. In 1986, the Northern Territory Education Department offered a print-making course at the Ngukurr community (Rebecca Hossack, 2002).“While others set about printing T-shirt designs, Riley asked for acrylic paints and embarked on a series of large mythological landscapes. Taking off from the bark-painting traditions of the area, he evolved his own highly individual style," Hossack (2002) stated.

Ginger Riley Munduwalawala’s ‘Nyamiyukanji, the river country’ (1997), synthetic polymer paint on cotton canvas. Image courtesy the Art Gallery of NSW, 2002.

Overall, First Nations’ paintings contain everything desired in authentic contemporary art. They have powerful aesthetics, historical context, symbolism, and a deep-rooted relationship to people, places and land. This is why major galleries and institutions nationally and globally are increasingly organising resources towards their Aboriginal art collections, which supports the global interest in the sales and production of such beautiful works.